Farmer Mac

A GSE Financing Rural America

Investment case: Farmer Mac is a structurally advantaged and low-cost source of financing for the farming and broader U.S. rural infrastructure industry with the potential to grow its earnings by 8-10% annually over the next few years, with room for earnings multiples expansion from 9x to 12x P/E.

What do Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch and Bill Ackman have in common?

Of course, they are investing legends.

More relevant to this deep dive, though, each had a love-hate relationship with Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), financial institutions created by the U.S. government to provide liquidity to targeted industries like housing, student loans and agriculture.

While there are a few of these GSEs, four were relevant in public markets: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Sallie Mae (no longer a GSE) and Farmer Mac (our current company of interest).

Peter Lynch - 1980s and 1990s

In his book, Beating the Street, Peter Lynch dedicated an entire chapter to his investment in Fannie Mae:

“Every year since 1986, I’ve recommended Fannie Mae to the Barron’s panel…I touted it in 1986 as the “best business, literally in America…it has a quarter of the employees of Fidelity and 10 times the profits.” - Beating the Street by Peter Lynch.

However, after the late 1990s, he never mentioned his bullishness in Fannie Mae.

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger - 1980s and 1990s

Buffett and Munger rarely promoted their positions publicly, but Freddie Mac was an exception.

Through Berkshire Hathaway and Wesco, they accumulated the maximum allowed stake, and in the 1988 Wesco annual letter, Munger outlined his investment thesis for Freddie Mac:

“Freddie Mac earns fees and ‘spreads’ while avoiding most interest rate-change risk.” - 1988 Wesco annual report by Charlie Munger.

By 2000, both Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were sold by Berkshire Hathaway and in 2001, they discussed that there were “certain things” in their operations they were no longer comfortable with (more on this in section 1).

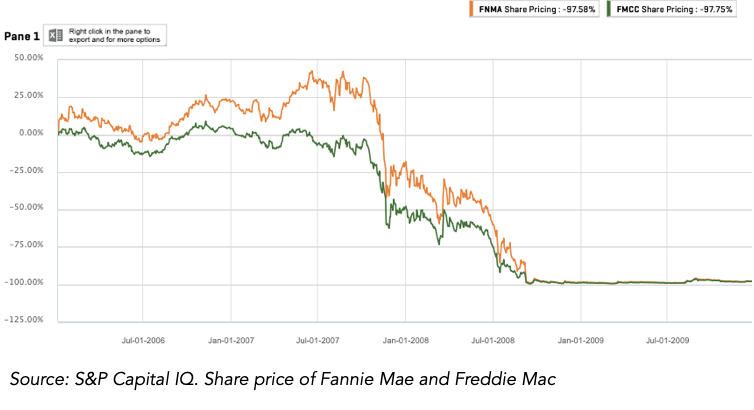

Seven years later, both companies were placed into conservatorship due to their exposure to the subprime mortgage market, with shareholders losing virtually all of their money.

Bill Ackman - 2000s and 2020s

Yesterday, (18th November 2025), Bill Ackman laid out a detailed presentation and long-term plan for bringing both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac back to public markets, following a 104-page presentation earlier in January.

But Ackman’s involvement with GSEs began long before that. In 2002, he shorted Farmer Mac, the smallest of the group. Five years later, he also shorted both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

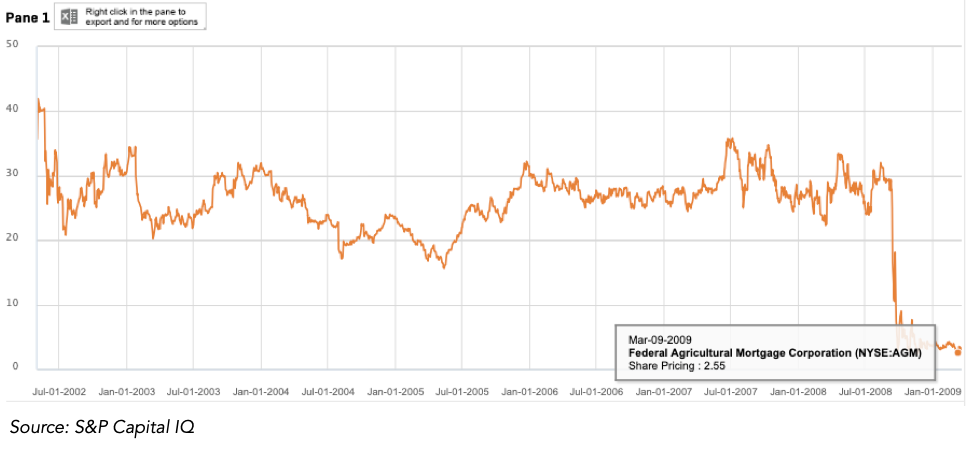

His 48-page short report on Farmer Mac highlighted weaknesses in corporate governance, delinquency rate and substandard loans underestimation, among other topics. By March 2009, seven years later, Farmer Mac’s stock was down by 92%.

Ironically, the share price decline wasn’t caused by the high-risk issues Bill Ackman identified, but by the supposedly low-risk investments in preferred stock and senior debt securities of Fannie Mae and Lehman Brothers, a combined $110 million investment loss or 40% of its then 2008 market cap.

The involvement of these investing greats immediately grew my interest in GSEs, and while both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac get all the headlines given the potential IPO case, lately I’ve been studying, and recently purchased shares of the smaller GSE, Farmer Mac - yes, despite the near-death experience in 2008, it survived! For context:

An investor who bought Farmer Mac shares just before its 92% drawdown in 2008 would have returned 506%, outperforming the S&P 500 (362%) since then.

With dividends reinvested, Farmer Mac shares have returned 16,109% since its 1994 IPO, a 17.4% annualised return.

Market cap (As of 19th November 2025): $1.75 billion

Jenga IP 2029 estimated market cap: $3.27 billion

Potential IRR (including dividends): 19% IRR

Jenga IP quality rating: 72.1 (moderate moat)

Of course, past performance alone tells us nothing about its future investment case. And given the complexity of GSE structures, history, incentives, and balance sheet structure, understanding Farmer Mac requires unpacking decades of context, regulation and industry economics. In this deep dive, I will explore:

Table of Contents

History and purpose of GSEs: A historical perspective into the creation, value creation and destruction of GSEs, their role in the financial crisis, Sallie Mae’s privatisation and an overview of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mae under conservatorship.

Farmer Mac’s history in focus: A deeper analysis of Farmer Mac’s history, value creation to the agricultural industry, its business partners, corporate governance and analysis of Farmer Mac before, during and after the financial crisis.

The U.S. agricultural industry: An overview of the U.S. agricultural industry, market share of farm debt and debt use, key trends and drivers of farm land value and net cash farm income, and how these impact Farmer Mac.

Business model and economics by segment: A breakdown and discussion of Farmer Mac’s business model by industry application - Farm & Ranch, Corporate AgFinance, Power & Utilities, Broadband Infrastructure and Renewable Energy. Key operational trends and profitability drivers, assessment of their net effective spread and overall business volume growth.

Business model and economics by assets: A breakdown and discussion of Farmer Mac’s business model by its financial securities - Loans, AgVantage securities, Long-term standby commitments to purchase (LTSCPs), guarantee fees and securities and agricultural mortgage-backed securities.

Growth potential: A detailed breakdown of its growth potential by company segment, assessing its potential long net effective spread, outstanding business volume and core earnings by division to 2029.

Other risks and challenges: Assessment and how I factor key risks such as asset-liability mismatch, delinquencies and sub-standard loan rates and current measures to gauge and limit risks. An overview of other potential risks, such as operational risks, corporate governance and growth.

Valuation: A breakdown of my book value and earnings-based valuation model based on business projections to 2029.

Conclusion: Final thoughts on Farmer Mac and lessons on investing in financials.

History and purpose of GSEs

Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) have been one of the most influential creations in the American financial sector, playing a key behind-the-scenes role in the financial freedom of home owners, farmers and students. At the balance sheet and operational level, these companies are quite complex; their annual reports are masterclasses on complex financial securities like callable debt, interest rate swaps, and asset-liability management, among others. However, their success lies in three key factors:

Access to cheap and sustainable capital

Law of large numbers

“Perceived” government guarantee

Access to cheap and sustainable capital

Before Fannie Mae’s founding in 1938, the U.S. mortgage terms were short-term, with 3-5 year mortgages versus 30-year mortgages today, highly fragmented and lacked a well-structured secondary market. The great depression caused a widespread default in loans and bank failures, and to support the housing market, the Roosevelt government created the Federal Housing Administration (1934) and Fannie Mae (1938) to support the market by insuring and buying loans.

Initially, funding came directly from the U.S. government, but by 1968, it was split into two entities: Ginnie Mae, which remained government-owned and Fannie Mae, which would later publicly list its shares. With its GSE status and unlike banks, Fannie Mae could access capital markets at rates that often matched treasury yields. GSEs also aren’t funded with customer deposits like banks, meaning they don’t have to worry about potential bank runs.

Law of large numbers

Over time, as the funding and loan books grew, the GSEs developed more creative ways to manage risk, ensuring their balance sheets were flexible enough to manage sharp interest rate changes and minimise asset-liability mismatches.

1970s (Mortgage-Backed Securities): As AUMs grew, the GSEs began creating mortgage-backed securities (MBS); lenders like banks would sell their loan books to GSEs like Fannie Mae and get immediate cash in return to then purchase even more loans. The GSEs would then pool thousands of mortgages, sorted by specific characteristics such as interest rates, maturity and borrower type (geography, loan-to-value ratio, age, etc). These pools are then sold to investors, with Fannie Mae guaranteeing timely payment and interest, even if borrowers default. The cycle is then repeated, and over time, scale becomes a significant advantage; the larger the asset base, the less overall risk, just like with insurance companies.

1980s (callable debt): A key risk is if the underlying borrower decides to pay early, a common situation when rates are expected to fall. It creates an issue as the prepayment risk could lead to an asset and liability mismatch (the prepayment becomes cash, while the liability is still at the higher interest rate), and to further solve this issue, GSEs began using callable debt, a debt that the GSEs can redeem before they mature. This gave them more time to shrink the liability when borrowers decided to repay early, and similar to MBS, they have a scale advantage. At times in the 1990s, callable debt represented 50-60% of the total long-term debt on Fannie Mae’s balance sheet.

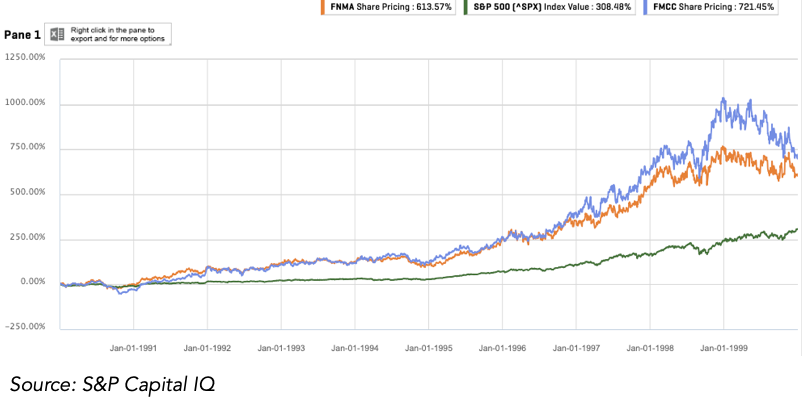

1990s (interest rate swaps and other derivatives): The 1990s were the golden decade for GSEs. Fannie Mae (614%), Freddie Mac (721%) and Farmer Mac (1,054%) each more than doubled the S&P 500 (308%), with their balance sheets ballooning during the decade. Fannie Mae, in particular, saw its total assets grow fourfold, and a key reason for this growth was the further flexibility and (over)confidence that derivatives created. To further hedge interest rates and prepayment risks, the GSEs could exchange fixed-rate payments for floating-rate payments (or vice versa), further neutralising any impact of interest rates.

“Perceived” government guarantee: The final key driver for GSEs was the perceived government guarantee. The U.S. government never explicitly guaranteed the publicly listed GSEs, but perception by employees, investors and other stakeholders (including the U.S. government itself) led to further growth as it meant even cheaper borrowing, more confidence in them and more market liquidity. This is a textbook case of moral hazard and led to the failure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Note, Freddie Mac was created to cater more towards smaller banks and thrift institutions.

From hedging risks to a profit centre: As a bid to drive even faster earnings growth, management at the GSEs turned the various hedging tools described above (interest rate swaps, MBS) into profit centres. By 1999, their ever complex balance sheets became even more complex and in 2002, Fannie Mae had to delay its annual report filings and pay fines as they later revealed they had misstated earnings to smooth its volatility.

“But the portfolio operations enabled both of those entities to use, in effect, government-related borrowing costs and sort of unlimited credit, to set up the biggest hedge fund in the world.” - Warren Buffett in 2008 on Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

Riskier loans: To meet housing objectives, the U.S. government added further pressure on Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae to buy and guarantee loans from riskier, subprime borrowers. At the depths of the late-2000s financial crisis, default rates peaked, leading to further losses for the GSEs.

Despite the advantages, the fate of the publicly listed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac turned out quite bleak, and as the chart portrays, their share prices virtually lost all of their value as they entered conservatorship.

Sallie Mae followed a different path from the other GSEs. By the mid-1990s, the U.S. wanted to remove the burden of student loans from taxpayers and completed the transition of Sallie Mae into a private company in 2004 and then its own entity by 2014. Its success depends on which stakeholder is asked. Shareholders would say it’s been successful, given the 11% annualised return since its spin-off in 2014, while most industry participants and customers argue it’s negatively added to the ongoing student-debt crisis.

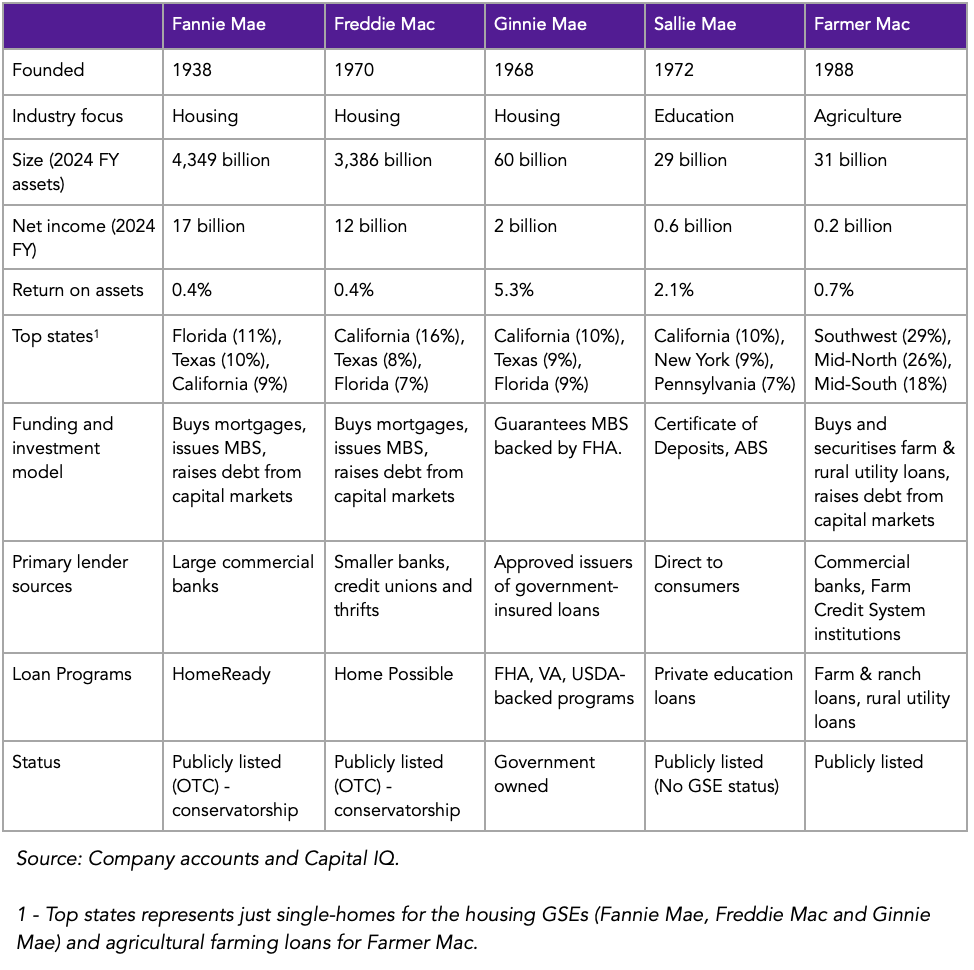

The table below explains the key differences between the five GSEs, highlighting some key stats such as their current return on assets, net income, loans by region and states, among other key attributes.

The GSEs are each quite different, and while Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae remain quite profitable, only Farmer Mac remains investable today as a true common stockholder, which sets us up for a deeper dive into its business operations.

2. Farmer Mac’s history in focus

Speaking to past Farmer Mac shareholders, you get two groups: those with positive comments and those with negative comments about them.

Positive past shareholders: They typically held Farmer Mac shares during the 1990s, 2010s or 2020s.

Negative past shareholders: They held shares between 2000 and 2010, a period its shares fell by over two-thirds of their value.

To understand why there’s such a stark contrast between its past shareholder base, I’ll discuss my findings from reviewing the history, split into four key periods.

Pre-1987

“To be a farmer was to be poor, but the early 1970s were a time of prosperity for many.” - Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, author of Growing up on a farm in the Long Ago.

GSEs tend to be created during periods of industry calamity, and Farmer Mac was no different, supporting the agriculture and rural farming industry, and we have to head back to the late 1970s.